- Home

- D. Watkins

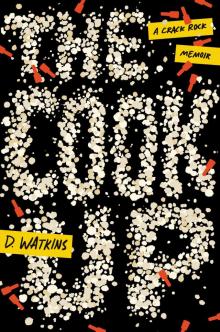

The Cook Up Page 2

The Cook Up Read online

Page 2

A steel battering ram ripped our door from its frame two days after his murder. Narcs buried my face in carpet while they tossed around my belongings. A bacon-colored captain stood over me. “The murder was drug related, son, this is normal procedure!” His coworkers looted our home, leaving only the items with no value. I managed to hold on to some jewelry but the bulk of our goods were placed on drug hold, or so they say.

The cops were so busy taking jewelry, and Sony products, they didn’t even notice the two-hundred-pound safe in the basement. Bip used to tuck money and gems in there, and he taught me how to open it in case of an emergency. But I couldn’t care less about that safe or any material thing in general. Bip—my influence, my definition of family, the person who made me inquisitive, the one who taught me everything from how to play basketball, how to save money, and how to study to how to drive, and how to protect my face in a fight—was a memory.

SHOOTERS

My homie Nick came through with weed to smoke every day. Nick is chubby with chubby features and covered in faded basement tattoos. He lives in a Yankees cap and all of his white tees touch his knees. He’s the first kid I met way back when we moved down to Curley Street.

I whipped him in a game of one-on-one over at Ellwood Park when we were twelve and he said, “You can beat me in basketball, but I bet you can’t beat me fighting!” We fought, both claimed victory, laughed it off, and have been tight ever since.

Weeks after Bip died, Nick would ask me about college and I’d just ignore him. I had thought about all of the schools I’d gotten into but I didn’t care about any of it. I had to shake Bip’s murder.

Every night, I’d hear Bip scream, “Deeeeeeeeeee, where’s my phone!” I’d pop up, and then check every room, flipping sofa cushions and rambling through desk drawers like a maniac until I realized that Bip was not there and he wasn’t coming back. Then I’d bolt downstairs, peek into the alleyway, unlock and relock every door and window before checking on his .357 under my couch, and making sure my .45 under my pillow was loaded.

Bip taught me how to shoot when I was thirteen. Nick tagged along too. We’d line cans up inside of the empty pavilion in the middle of Ellwood Park after hours and buck shots at them one by one.

“I’m only teaching you how to shoot for protection. Remember, any coward can use a gun,” said Bip, mangling logos dead in the center of every can. Nick tried to hold the gun sideways like the guys in hood movies. He eyed a Sprite can while extending the pistol—POP! The bang slung Nick to the ground with the gun flying in the opposite direction. He received more damage than the can he was aiming at.

“I’m good, Yo!” screamed Nick, popping up, rubbing his arms, pulling his dick and making sure that the rest of his body parts were still attached.

“That’s a lesson!” Bip laughed. “Never hold a gun like a dumb nigga in a hood movie! This ain’t Hollywood, this Holly-hood! Dee, you up next!”

I picked up the gun that embarrassed Nick and squeezed the handle with both hands, tight enough to feel my veins pop. It warmed my skin as remnants of smoke from Nick’s attempt swam past my target. The soda can was perfectly aligned with my front sight. I looked at Bip; he looked at the can and then gave me a nod.

I delivered two shots, the first hitting the can, the second hitting where the can once stood. “Lemme try again, Yo!” Nick yelled, still massaging his arm. I passed him the pistol.

“Good job, boy! But remember, anyone can shoot a gun, real niggas use these,” Bip said, holding up his fists like trophies.

I wish that statement was true, but I was smart enough to know that it didn’t matter if you were considered to be “real” or “fake”—people didn’t fight with their hands anymore.

COPING TACTICS

Ay Yo, Biggie my favorite rapper but he say some gay-ass shit like, ‘Girl, you look so good huh, I’ll suck on ya daddy dick’ and I’m like, ‘Yo! What type of homo shit is that?’” yelled Nick from downstairs.

“Word, that line is mad suspect,” I replied, digging in my ashtray, looking for a blunt butt to spark.

“I’m a call this weed and roll some pussy. I mean… You know what I mean, nigga. You want some weed and some pussy, right?” Nick said, flopping on the couch ass first.

“Yo, Dee, Biggie a handsome fat nigga like me. That’s why I fuck with him. He made fat niggas sexy, though, you feel me?”

I laughed as I went back upstairs and climbed back into my bed, wondering what it would be like not to feel. Emotions are unneeded baggage that won’t allow me to be anything but a broken person who weeps in isolation. If I was as smart as I thought I was, I’d be able to teach myself not to feel. My sheets smelled like bud and underarms. Bip’s RIP balloons were past deflated and sagging over my dresser.

“I’ma bring the blunt up to you, bro!” hollered Nick.

Nick tried his best to help me cope with losing Bip. His idea of coping meant good weed, lots of Belvedere, and being an ear even though I didn’t say much. He tried to make me laugh every day and sometimes it even worked. More importantly, Nick helped me move all of the books, sneakers, and everything else that belonged to Bip out of the house. Dump the clothes, dump the memories, dump the pain, or so I thought. Some of those memories remained undumpable: Bip’s bookstands, Bip’s push-up bars, the matching recliners we sunk into when watching playoff games, his spare car keys on my dresser.

His smell—Polo Blue—lurked around corners, his toothbrush, hairbrush, and flat razors. “Fuck is my razors at, D!” he’d yell on date nights. Bip’s half-eaten crab cake was still in the fridge, his boxes of Raisin Bran, Mistic Pink Lemonade iced tea—his official drink—his posters, his toiletries, and his pictures.

I had to get off of Curley Street.

Milton, the same guy who rented us the place on Curley, had a corner house in back of a alley for me on North Castle Street—about two miles north. The boarded-up homes that filled the neighborhood made it look like a crackhead resort.

He wanted six hundred dollars a month, which was cool. I thought I could look for a job while I lived off of the eight thousand and some odd dollars that I had saved up from Bip’s allowances. College could wait.

Nick needed a place too, so I told him that he could move in for three hundred dollars a month and we could split the utilities along with the cable bill straight down the middle. He was cool with that, so I signed the lease and paid the first three months in cash.

Nick sold a little weed too, when he could get it. It wasn’t the best or the worst—mid-grade with small traces of orange hair and every once in a while you found a seed. He was no Scarface but he raked in enough dough to cover his share of the bills, and if he couldn’t, we could always get money from Hurk.

Hurk and I met in the towers. His mom sucked dick for crack until she became too hideous to touch. By the time I was thirteen, her gums were bare, her skin peeled like dried glue, chap lived on her lips and she always smelled like trash-juice. Her last days were spent panhandling on Fayette Street and getting a puff or two off of old cigarette butts she found smashed in the pavement. Eventually AIDS took her out of her misery.

Hurk’s my age. When we were kids, his family was about a billion dollars below the poverty line. All of his jeans had shit stains because he didn’t have underwear or running water, and he had so many holes in his shoes that his feet were bruised. Shortly after we met, I started giving him clothes that I didn’t want and he stayed with us most nights. We became brothers.

At thirteen, Hurk started hustling for Bip and never looked back. He loved his job. Hurk was organized, and he worked harder than anyone else on the corner. Like a little Bip, Hurk beat the sun to work every morning—four a.m. in the blistering cold, with bright eyes and fists full of loose vials.

He never messed up the count and seized every advancement opportunity. His workload tripled after Bip passed, but he called every day and came by when Nick and I moved into the new place.

“Dee, how you holdin’ up, shorty

?” said Hurk.

“I don’t even know. Man, I been in the bed for weeks,” I replied.

“Naw, nigga, get out. Get a cut, nigga, go do some shit! Least you still alive!”

“You right,” I said as I sat on the edge of my bed.

“What the fuck, Yo, you cry every day?” Hurk asked.

“Naw, well no, shit, I dunno.”

“Yo, anyway I’m gonna murder dat nigga that popped Bip. Ricky Black bitch ass. You go live, nigga, get some new clothes, pussy or sumthin’.”

I picked my head for the first time in days. “I didn’t even know my bro had static with him.”

The drama that comes with murder made Hurk excited. He leaped from his seat.

“I don’t know why he killed Bip. But they saying it’s him, he was always a hata. But whatever, Yo, I’ma get dat nigga!”

I told him he was crazy, but I didn’t care. I wasn’t happy or sad, just indifferent and used to murder. I wouldn’t commit that murder—I’m not a killer. I am capable of hate. I hate Ricky or whoever did this, and I am a direct product of this culture of retaliation. A culture that did not allow me to sleep, eat, or rest until I know that Bip’s killer is dead. It didn’t even matter if Hurk or I killed Ricky or not because someone would eventually. Bip received love from almost every thug in the city, so someone would avenge his death.

“I gotta go, I got dope to sell, brova. I love you!” said Hurk, fixing his jeans, preparing to exit.

“Be careful,” I said.

“Nigga, I keep the ratchet on me,” he replied while lifting his sweatshirt to show me the gun planted on his waist. He also said that he had an HK in his backpack with a bunch of rounds that clicked against each other when he moved.

“Better to get caught with a hammer than without it, ya dig?” I said while showing him to the door.

“You should think about school, D. Bip would like that. Plus I won’t be around too much, Yo, I’m on the run for some bullshit. They sayin’ I shot somebody. Da cops kicked my girl’s crib in at four a.m. and everything!”

“Damn, you did it?”

“Who knows, but fuck the police, I’ll holler!” said Hurk, flapping on his hood and walking out.

A DIFFERENT WORLD

Going to away to school would have been too much for me three months after Bip’s death. Campus housing, adjusting to life in another city, and late registration all while wearing my depression like an overcoat was a reality I couldn’t handle, so I decided to attend Loyola, a local school on the edge of Baltimore.

I always thought college would be like that show A Different World. Dimed-out Lisa Bonets and Jasmine Guys hanging by my dorm—young, pure, and making a difference. I’d be in Jordans and Jordan jerseys or Cosby sweaters like Ron and Dwayne Wayne, getting A’s and living. No row homes, hood-rats, housing police, or gunshots—just pizza, good girls, and opportunity.

Loyola was a GAP commercial—miles and miles of grass, new construction, and healthy smiles. I saw kickball and flag football and people holding hands. A universe of white and Asian faces smirked at me as I walked across campus the first day. This was a different world, but not the one I was looking for.

There were some other black guys there, but they weren’t black like me. They spoke proper English, called each other dude, wore pastel colored sweaters, Dockers, and boat shoes, carried credit cards, chased Ugg-booted-white girls, played sports other than basketball and talked about Degrassi—What the fuck is Degrassi?

I wore six braids like Iverson, real Gucci sweat suits like my brother, and about a fifteen-thousand-dollar mixture of my and Bip’s old jewelry. It was my first experience interacting with other races, and that, combined with my Rasta weed habit, made me paranoid so I talked Nick—who had dropped out of middle school long ago—into hanging around campus with me.

“Yo, Dee, if any of these people act dumb, even the da principal, tell me. Swear to God I’ll fuck ’em up for you, Yo.”

“Colleges have deans, Nick, not principals, but I guarantee I won’t have any problems here.”

Each day, I’d float through Loyola clean and high. Some of the students were racist—but not to my face, and it probably wasn’t their fault, most of their parents gave them racism as a first gift. A few of my professors looked at me as if I was speaking a different language when I answered questions. My philosophy teacher, a tweed coat–wearing dickhead was the worst; every class he’d say, “What sport did you play to get into here?” I honestly thought about having Nick pistol-whip him, but he was only a pedestrian on my road to bigger goals.

I started meeting people and even tried to adjust to the campus culture by attending basketball games and buying a gray Loyola hoodie. I bought Nick a black one. Together we’d sit through home games, underwhelmed by the basic style of play and unaffected by the school spirit that shook the gym. Loyola students get excited over made free throws and baseline jump shots. Hood dudes like us need to see thrills: dunks, spin moves, shit talking, finger pointing, and ankle-breaking crossovers.

Eventually, I met some cool white boys to smoke weed with. Tyler was a freshman like me but already had a hold on the campus. Girls giggled when he spoke, and most of the other freshmen lived and died for his approval. I saw him around a few times but initially we met in the Athletic Center. I was shooting jumpers and Nick was rebounding for me. Tyler walked up and said, “Nice shot. You guys gamble?”

“Shoot his head off, Dee! Shoot his head off, Dee!” chanted Nick. Tyler and I went five dollars a shot for an hour or so and I think he beat me out of two or three hundred dollars. I paid him and he gave me a hundred back.

“What’s this for?” I said, rejecting the money. He explained that he had gambled with black guys before and he noticed that the winners always give the losers a little something back. Then he said: “Besides, you guys smell like Jamaicans! Can I get some of that?” The three of us walked back to Nick’s Camry and smoked some joints. Tyler thought the bud was decent; Nick and I always had it so we exchanged numbers.

Sometimes we smoked and talked trash to girls together, or beat the shit out of the squares that hung around in the gym in basketball. Tyler even took me to his spot in Bolton Hill, a neighborhood filled beautiful brownstones that ran from $300K to almost a million.

Tyler liked Jay Z, 2Pac, and watched Above the Rim, just like me. I turned him on to chicken cheese steaks with hot sauce from Mama Mia’s. He exposed me to the richer parts of city like Mount Vernon and Guilford, where there wasn’t a black person in sight—places I didn’t even know existed.

I understood all of his white boy slang like puke or dude or riffle, which means to steal. White boy slang is easy. But I had to explain some language to him that he couldn’t pick up in context—like unk meaning uncle, everybody’s name is Yo or dummy, and how we say dug instead of dawg or dog and Vick. White people liked to buy eighths of weed but black people buy Vicks. A Vick is seven grams and we call them Vicks because Michael Vick wore number seven.

I really liked Tyler but most of his friends were hard to take. They’d invite me and Nick to campus parties. We’d walk in and the mood would change. They’d reference Dr. King and then Dr. Dre, and call us bro and brotha, and give us too many handshakes. They tried to imitate us so we felt more comfortable, but it just felt condescending. Luckily, we never got into any fights and the N-word never slipped out. The parties got old to us really quick so we stopped going.

My mother being super proud was the best part. She’d tell all of her church friends that I was doing well in School and hit me on the jack like “College man, you need anything?” I’d always say no, and pretended like everything was ok. An artificial front that I started believing myself.

I faked like doing homework and adjusting to this new world helped me deal with the loss of Bip, but in reality I still had sleepless nights where I sat in the park until the sun came up, wondering why I was alive, why Hurk had such a short temper, why couldn’t Nick study and be a student too, and w

hy I didn’t get a chance to tell my bro what he meant to me. By mid-semester I was sick of school. The work wasn’t hard, but it was boring as that show MASH. I feel like anybody can listen to teacher, read a book, and then solve a problem. And trying to assimilate was even more exhausting.

What would my brother say if he saw me hanging around the cafeteria with Zack Morris and Carlton Banks, laughing at jokes I hated, listening to stories that bored me, going to wack basketball games, slowly conforming—being a good Negro. What would he say if he caught me referencing Degrassi? Bip didn’t want me in the streets, but I know he didn’t want this—we were raised by Biggie, Spike Lee, Pac, NWA, and Public Enemy, not this Wayne Brady shit.

So I said fuck it.

THAT RED SAFE

That first semester at Loyola, I was down to about $2,900, sharing a car with Nick, and had no income. Pain stared back when I glanced in the mirror and basically my whole demeanor looked manic-depressed.

I was sick of school and knew it was time to crack Bip’s safe. I could ease some pain with the cash and look for a job while I figured this life shit out. The key for me was not to blow all the money on stupid things like cars, clothes, and fun—really the only stuff eighteen-year-olds cared about.

The safe was red and rusted. It had to weigh about two hundred pounds. I remember when Bip bought it from a pawn shop on Monument Street. The guy wanted five hundred dollars but he talked him down like, “Man, you know what I spent up in here? Hook a brotha up and knock a little off. You want me to have a lil something to put in there, right?”

Those guys at the shop discounted it because they loved Bip. Then they spent about fifteen minutes explaining the functions and talking about how it was fireproof and could probably survive a nuke. It took two fiends to lift it, which says a lot because crack gave junkies superhuman strength.

The Cook Up

The Cook Up